Zoloft®

Mechanism of Action

- The mechanism of action of ZOLOFT® is presumed to be linked to its specific inhibitor of neuronal serotonin (5 HT)CNS uptake. It has only weak effects on norepinephrine and dopamine neuronal reuptake.1

- Studies at clinically relevant doses in man have demonstrated that ZOLOFT® blocks the uptake of serotonin into human platelets1

SSRI mode of action: In this figure, the serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) portion of the SSRI molecule is shown inserted into the serotonin reuptake pump (the serotonin transporter, or SERT), blocking it and causing an antidepressant effect.2

Adapted from Stahl SM, 2013

CNS: Central Nervous System, SSRI: Selective Serotonin reuptake inhibitors, 5-HT: 5-Hydoxytryptamine, SERT: the serotonin reuptake transporter

References:

- Zoloft(Sertraline), SmPC, May 2022.

- Stahl SM. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

EFFICACY

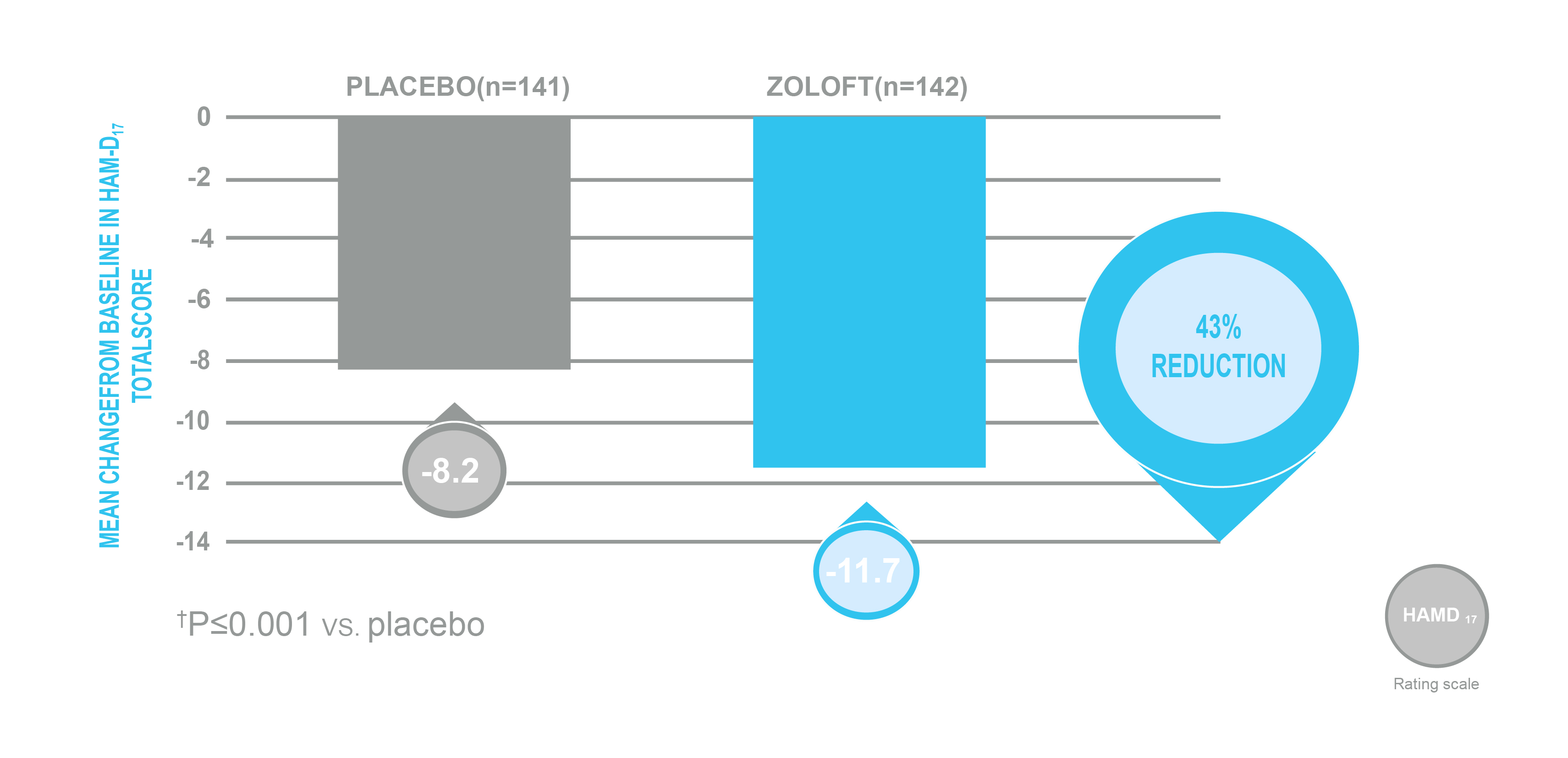

ZOLOFT® demonstrated significant efficacy in treating depressive symptoms in patients with MDD.1

Significant improvements of depressive symptoms with ZOLOFT® vs placebo at Week 8, as measured by 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) total score.*1

Mean change from baseline in HAM-D17 total score at Week 81

Adapted from Reimherr FW, et al. 1990.

* A double-blind, randomized, placebo-and active-controlled, parallel-group study of the efficacy and safety of ZOLOFT® 50-200 mg/day (n=149), amitriptyline 50-150 mg/day (n=149), and placebo (n=150) in patient with DSM-III-defined major depression. After a 7- to 14-day washout period, patients were required to have a HAM-D17 total score ≥18 with a <25% decrease from screening, and a higher score on the Raskin Depression Scale than on the Covi Anxiety Scale. The mean baseline HAM-D17 total score was 23.29 for ZOLOFT® and 23.25 for placebo. Primary efficacy analyses included a change from baseline in HAM-D17 total score.

Amitriptyline data not shown.

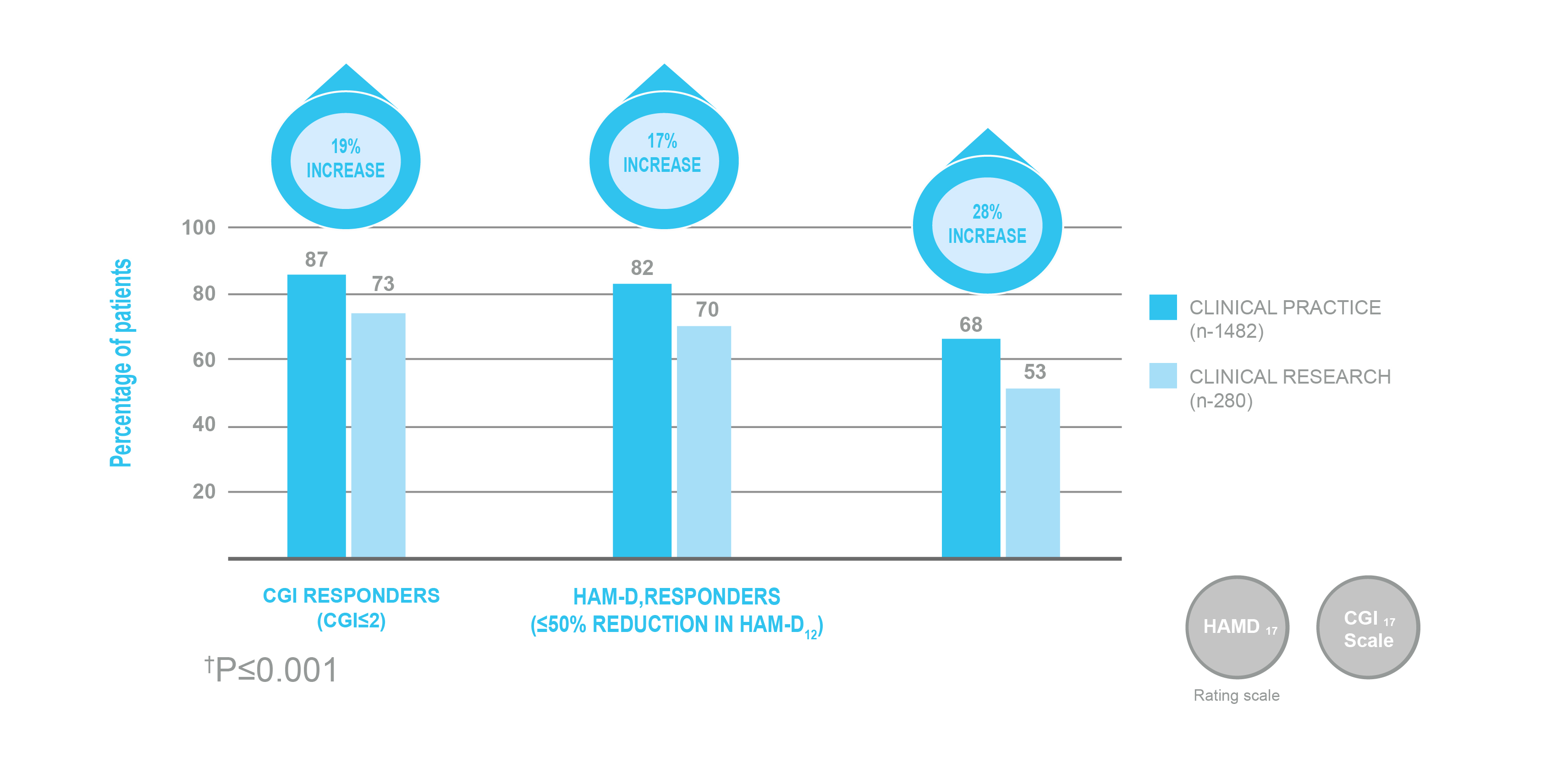

ZOLOFT® demonstrated greater therapeutic response in clinical practice than in the clinical research setting.2

ZOLOFT® demonstrated significantly better outcomes in clinical practice than in controlled studies.*2

Comparison of outcomes in clinical practice and clinical research setting2

Adapted from Lydiard RB, et al. 1999.

* Results from a comparison of a large-scale, open-label, 8-week study of ZOLOFT® 50-200 mg/day in adult patients 21-65 years old with DSM-III-R defined MDD and a HAM-D17 score ≥18 (n=1482) vs pooled results of 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (n=280). The mean baseline HAM-D17 total score was 21.8 in the clinical practice population and 22.6 in the clinical research population. Overall response was assessed with HAM-D17 and CGI-I scores. Response was defined as ≥50% reduction from baseline in the HAM-D17 total score and achieving a CGI-I score of 1-2 at study endpoint. Remission was defined as HAM-D17 total score ≤7 and CGI-I score of 1 or 2 at study endpoint.

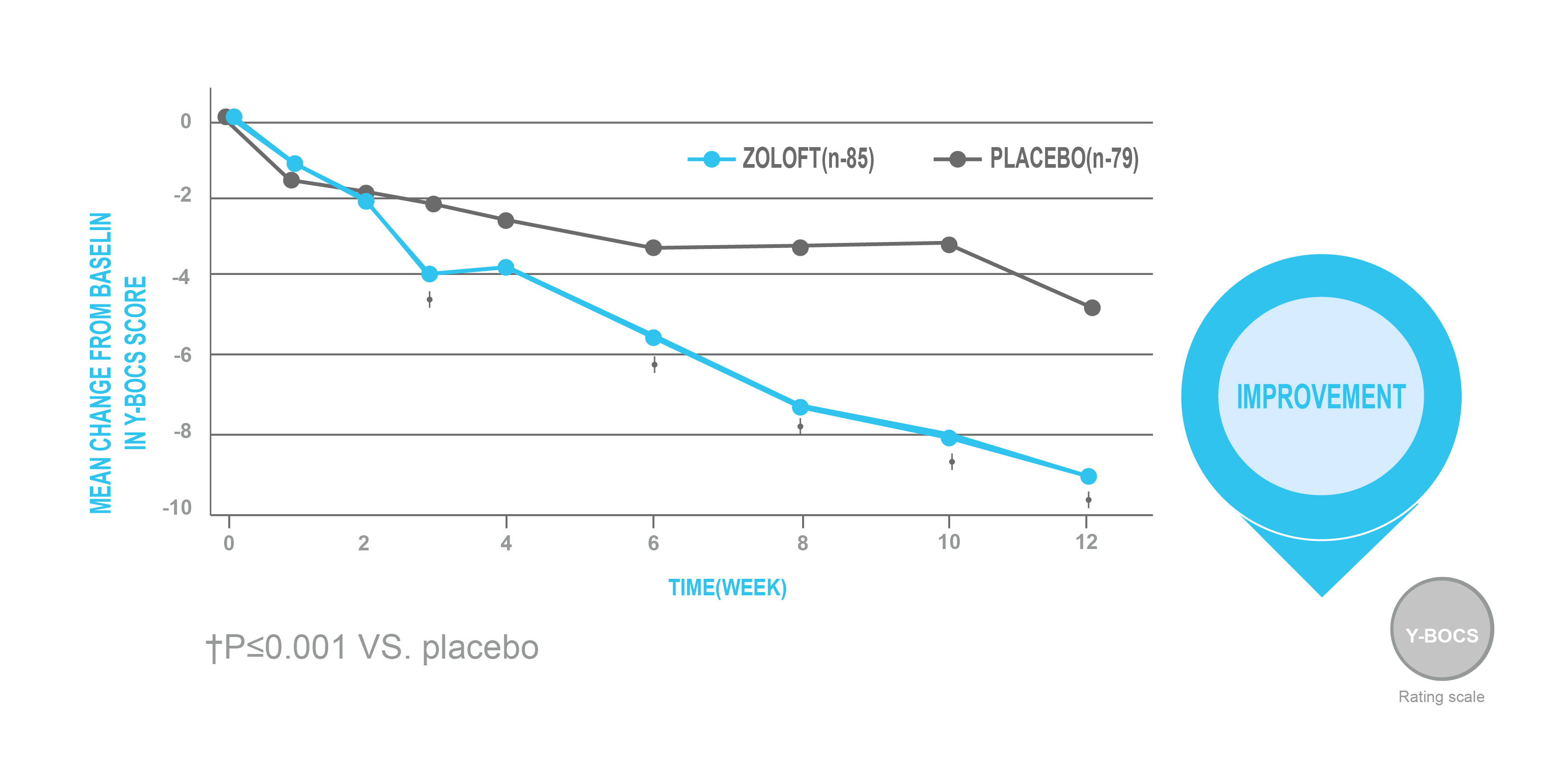

ZOLOFT® demonstrated a significant reduction in OCD symptoms.3

ZOLOFT® provided significant reductions in OCD symptoms as early as Week 3, as measured by the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS).*3

Change from baseline in Y-BOCS scores over 12 weeks3

Adapted from Kronig MH, et al. 1999.

* A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of ZOLOFT® 50-200 mg/day (n=85) and placebo (n=79) in outpatients with moderate-to-severe OCD with a duration of illness ≥1 year. Patients had a Y-BOCS score ≥20, a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale score ≥7, and a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Severity Scale ≥4. The mean baseline Y-BOCS score was 25.21 for ZOLOFT® and 25.05 for placebo. Primary assessments included a change from baseline in Y-BOCS score.

Late life depression

ZOLOFT® versus Fluoxetine.4

In a study of outpatients aged 60 years or older with MDD, Sertraline was found to be equally effective as fluoxetine for treating depressive symptoms.4

Effects of comorbidity and polypharmacy on Sertraline use in elderly patients with MDD.5

Results from an observational study of elderly depressed outpatients indicate no significant differences in adverse events with or without concurrent medications and confirm the effectiveness and safety profile of Sertraline in routine clinical practice.5

ZOLOFT® can also be used to treat a broad range of other anxiety disorders6:

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD)

- Panic disorder (PD)

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

MDD: Major Depressive disorder, CGI: Clinical global impression, OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

References:

- Reimherr FW, Chouinard G, Cohn CK, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of sertraline: a double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990 Dec;51(Suppl B):18-27.

- Lydiard RB, Perera P, Batzar E, et al. From the bench to the trench: A comparison of sertraline treatment of major depression in clinical and research patient samples. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;1(5):154-162.

- Kronig MH, Apter J, Asnis G, et al. Placebo-controlled, multicenter study of sertraline treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999 Apr;19(2):172-176.

- Newhouse PA, Krishnan KR, Doraiswamy PM, et al. A double-blind comparison of sertraline and fluoxetine in depressed elderly outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;61(8):559-568.

- Arranz FJ, Ros S. Effects of comorbidity and polypharmacy on the clinical usefulness of sertraline in elderly depressed patients: an open multicentre study. J Affect Disord. 1997 Dec;46(3):285-291.

- ZOLOFT® (sertraline). Prescribing Information. Oct 2021.

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

SAFETY & TOLERABILITY

ZOLOFT® is well tolerated in patients with acute myocardial infarctions (MI) and unstable angina.1*

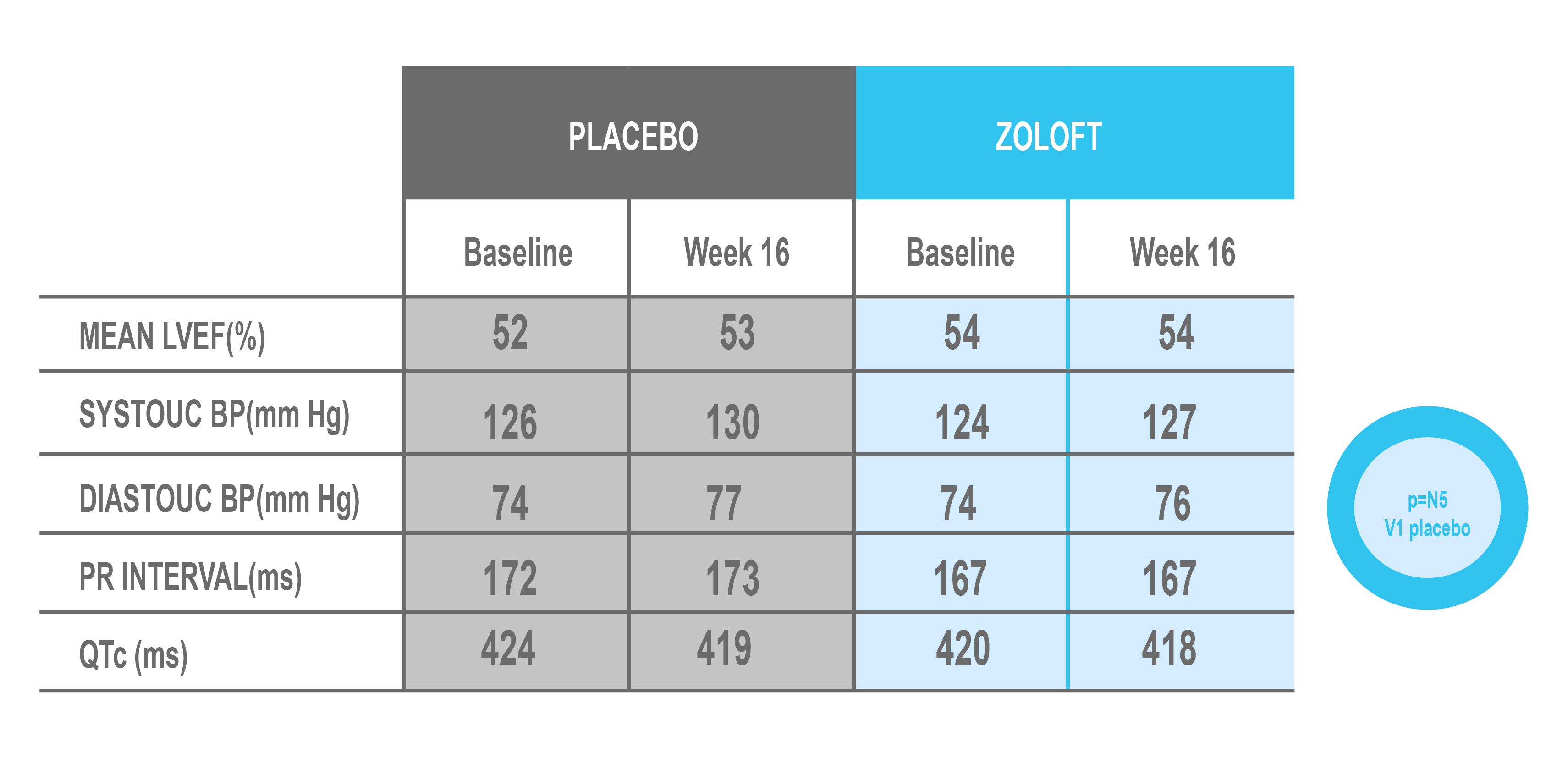

In MDD patients with recent myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina, no significant changes in cardiac function were observed with ZOLOFT® over 16 weeks vs placebo.1*

Cardiac safety profile at baseline and after 16 weeks1

Adapted from Glassman AH, et al. 2002.

* A 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of ZOLOFT® 50-200 mg/day (n=186) and placebo (n=183) in DSM-IV-defined MDD patients hospitalized for a recent diagnoses (within 30 days) of MI or unstable angina. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

There was no statistically significant difference in LVEF between patients receiving sertraline or placebo.1*

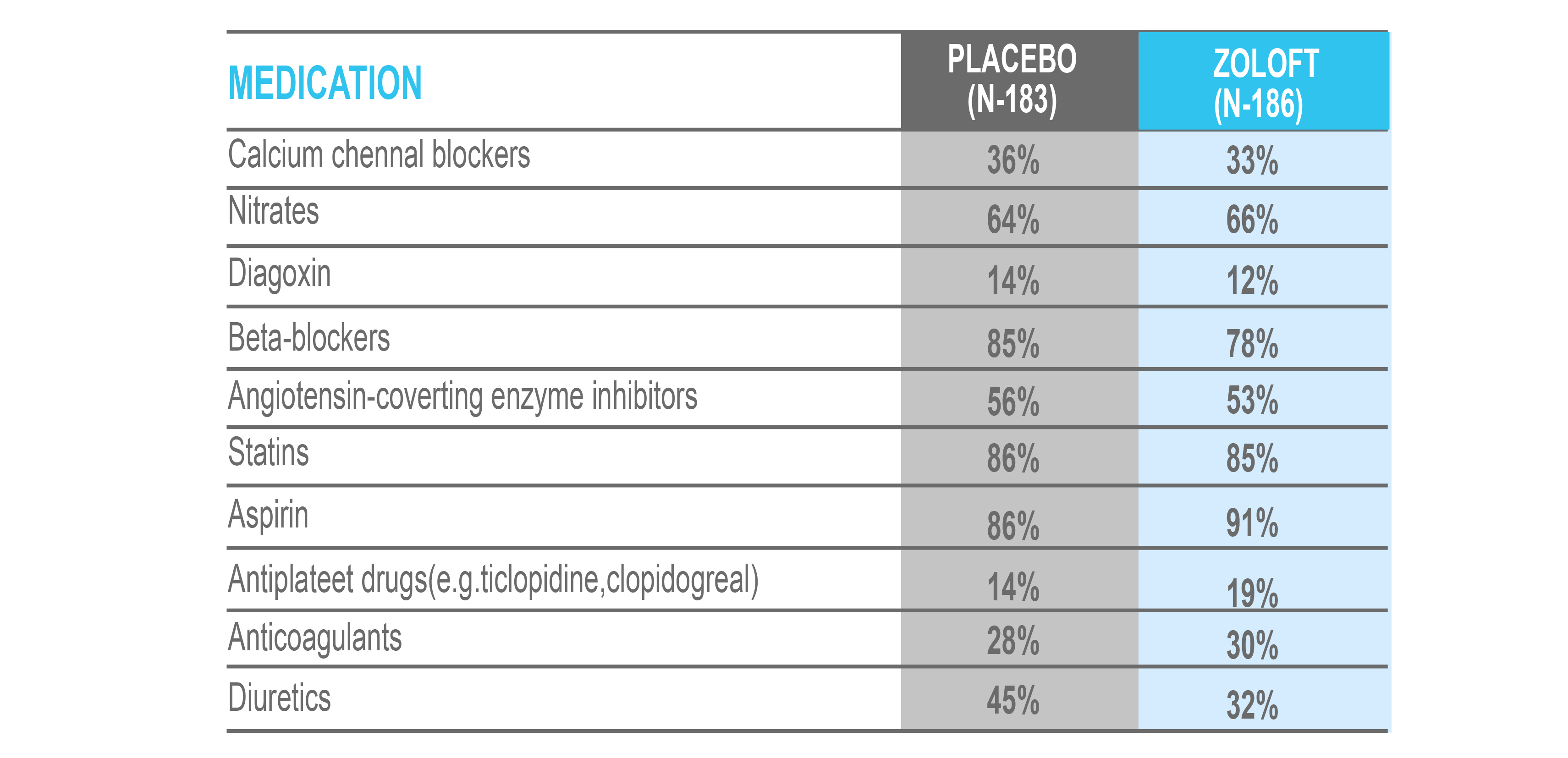

Frequency of concomitant cardiovascular medication use1

Adapted from Glassman AH, et al. 2002.

* A 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of ZOLOFT® 50-200 mg/day (n=186) and placebo (n=183) in DSM-IV-defined MDD patients hospitalized for a recent diagnoses (within 30 days) of MI or unstable angina. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

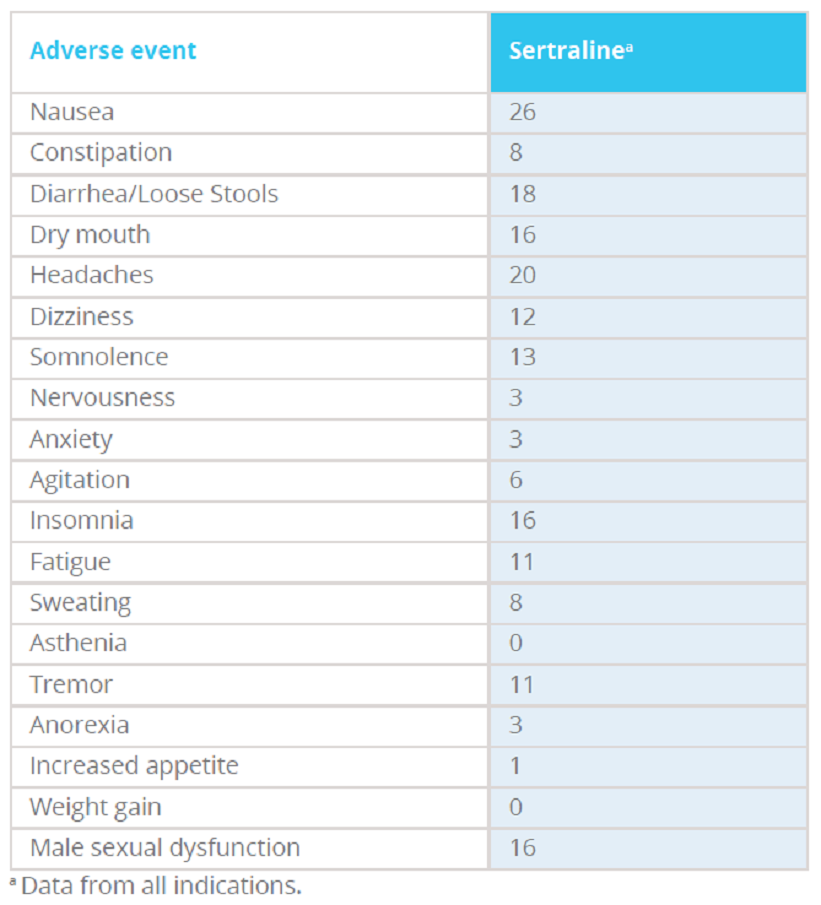

ZOLOFT® Prevalence of adverse events.2

Unadjusted frequency (%) of common adverse events as reported in product monographs.2

Adapted from CANMAT 2016 clinical guidelines.

ZOLOFT® drug interaction profile.

In placebo-controlled studies, ZOLOFT® demonstrated low incidences of adverse events.3

ZOLOFT® is neither an exclusive substrate nor a strong inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzyme isoforms.3

Important drug interaction with Zoloft

- In formal interaction studies, chronic dosing with ZOLOFT® 50 mg daily showed minimal evaluation (mean 23%-37%) of steady-state desipramine plasma levels (a marker of CYP 2D6 isoenzyme activity)4

- ZOLOFT® has the potential for clinically important 2D6 inhibition. Consequently, the concomitant use of a drug metabolized by P450 2D6 with ZOLOFT® may require lower doses than usually prescribed for the other drugs.5

References:

- Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHEART) Group. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. 2002 Aug 14;288(6):701-709.

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540-60

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(Suppl 10):9-118.

- ZOLOFT® (sertraline). SmPC, May 2022.

- ZOLOFT® (sertraline). Prescribing Information. Oct. 2021.

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

Posology & Method of Administration

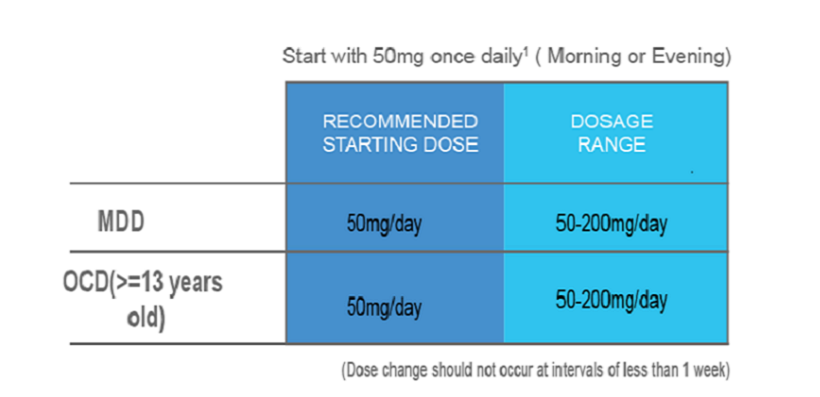

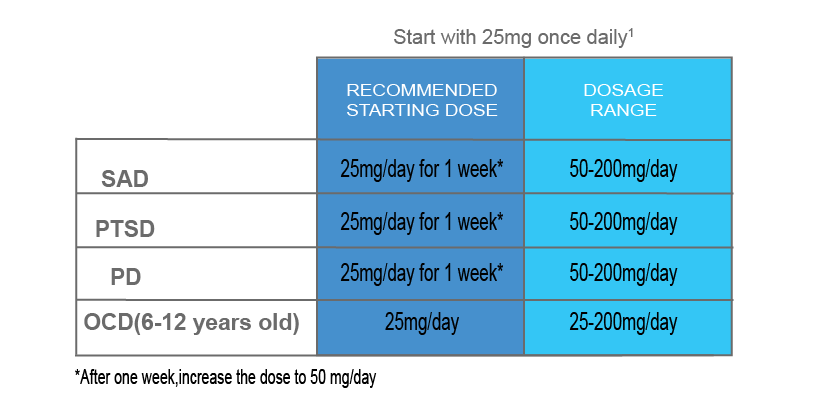

ZOLOFT® flexible, once-daily dosing across a number of indications.1

MDD: Major depressive disorder, OCD: Obsessive compulsive disorder, PMDD: Premenstrual Dysphoric disorder, SAD: Social anxiety disorder, PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder, PD: Panic disorder

Reference:

- ZOLOFT® (Sertraline), SmPC, May 2022.

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

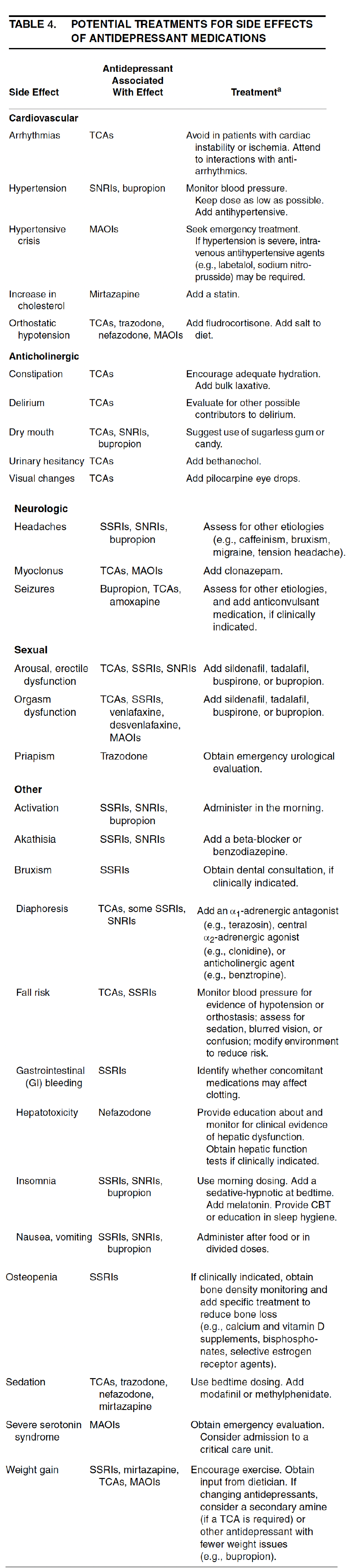

Treatment Guidelines

Relevance of the APA clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of patients with MDD on our portfolio of medicines: Zoloft® and Effexor

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATIONS 1

Each recommendation is identified as falling into one of three categories of endorsement, indicated by a bracketed Roman numeral following the statement. The three categories represent varying levels of clinical confidence:

[I] Recommended with substantial clinical confidence

[II] Recommended with moderate clinical confidence

[III] May be recommended on the basis of individual circumstances

Principles of psychiatric management of Major Depressive Disorder:

The Psychiatric management of an individual with possible major depressive disorder involves the following activities:1

- Establish and maintain a therapeutic alliance - collaborate with the patient in decision making and attend to the patient’s preferences and concerns about treatment [I]

- Complete the psychiatric assessment - Patients should receive a thorough diagnostic assessment in order to establish the diagnosis of major depressive disorder, identify other psychiatric or general medical conditions that may require attention, and develop a comprehensive plan for treatment [I]

- Evaluate the safety of the patient – A careful and ongoing evaluation of suicide risk is necessary for all patients with major depressive disorder [I].

- Establish the appropriate setting for treatment - determine the least restrictive setting for treatment that will be most likely not only to address the patient’s safety, but also to promote improvement in the patient’s condition [I]

- Evaluate functional impairment and quality of life - Major depressive disorder can alter functioning in numerous spheres of life including work, school, family, social relationships, leisure activities, or maintenance of health and hygiene. The psychiatrist should evaluate the patient’s activity in each of these domains and determine the presence, type, severity, and chronicity of any dysfunction [I].

- Coordinate the patient’s care with other clinicians

- Monitor the patient’s psychiatric status – The patient’s response to treatment should be carefully monitored [I].

- Integrate measurements into psychiatric management

- Enhance treatment adherence

- Provide education to the patient and the family

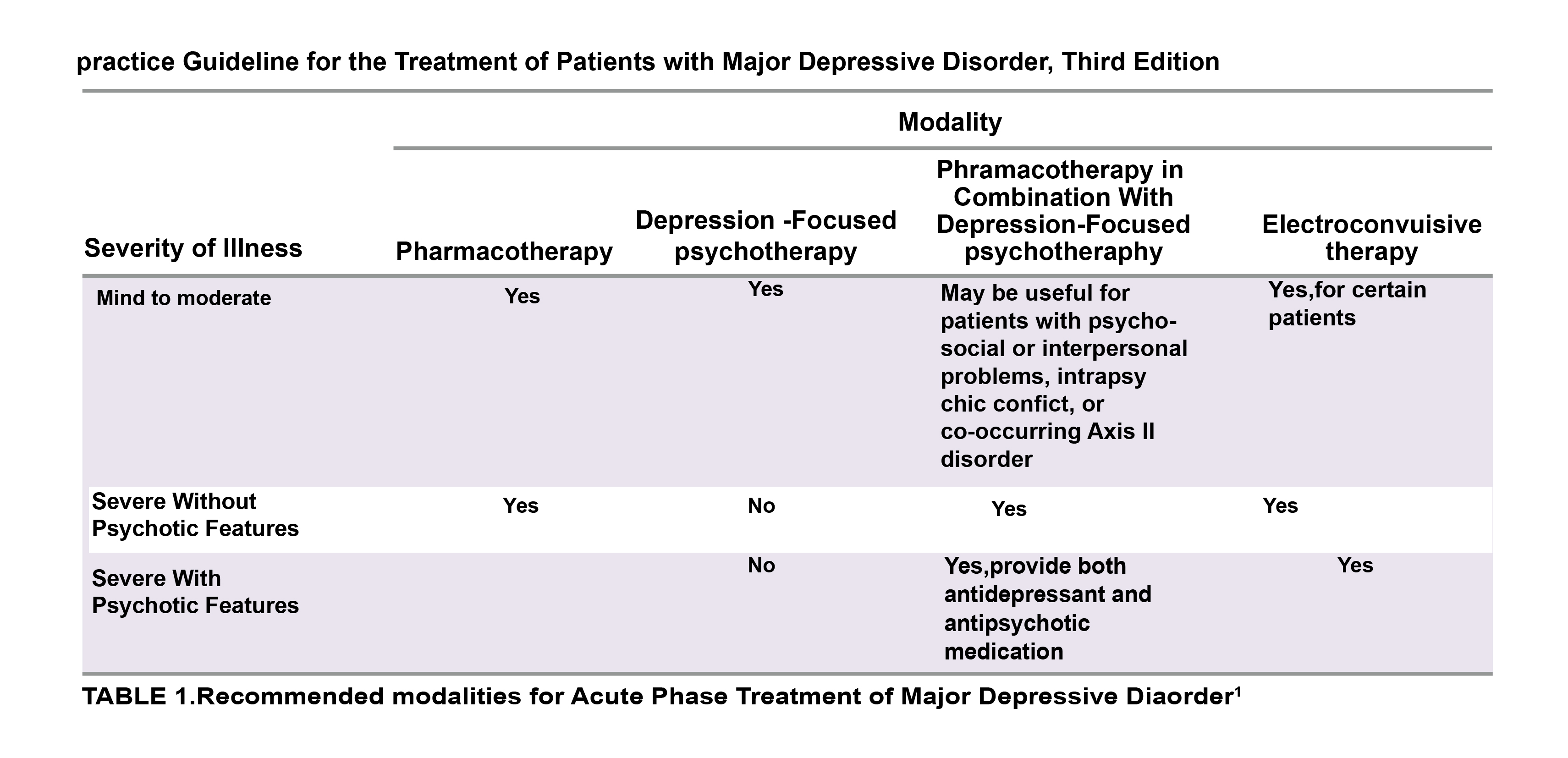

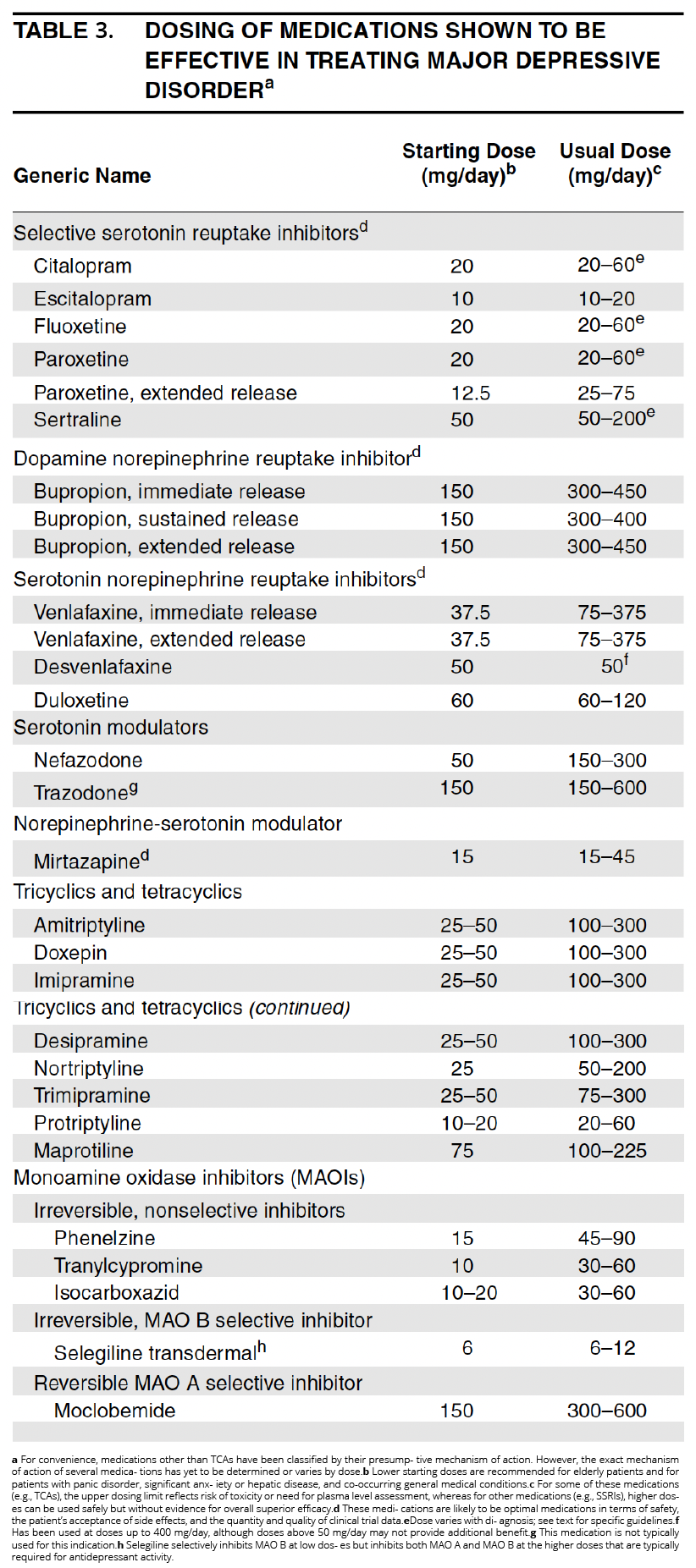

Pharmacotherapy of Major Depressive Disorder1

Acute phase1

Selection of an initial treatment modality should be influenced by clinical features (e.g., severity of symptoms, presence of co-occurring disorders or psychosocial stressors) as well as other factors (e.g., patient preference, prior treatment experiences) [I].1

- Treatment in the acute phase should be aimed at inducing remission of the major depressive episode and achieving a full return to the patient’s baseline level of functioning[I].

- For most patients, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), mirtazapine, or bupropion is optimal [I].

- Once an antidepressant medication has been initiated, the rate at which it is titrated to a full therapeutic dose depends upon the patient’s age, the treatment setting, and the presence of co-occurring illnesses, concomitant pharmacotherapy, or medication side effects [I].

- If antidepressant side effects do occur, an initial strategy is to lower the dose of the antidepressant or to change to an antidepressant that is not associated with that side effect [I].

- The combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication may be used as an initial treatment for patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder [I]

*Initial approached to treatment-emergent side effects include decreasing or discontinuing the medication and changing to another antidepressant with a different side effect profile. Treatments included here are additional measures

- All anti-depressant medications appear to require at least 4–6 weeks to achieve maximum therapeutic effects.1

- Combined treatment with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may be considered a treatment of first choice for patients with major depressive disorder with more severe, chronic, or complex presentations. Combining family therapy with pharmacotherapy has also been found to improve posthospital care for depressed patients.1

Continuation phase

- Although the number of Randomized controlled trials of antidepressant medications in the continuation phase is limited, the available data indicate that patients treated for a first episode of uncomplicated major depressive disorder who exhibit a satisfactory response to an antidepressant medication should continue to receive a full therapeutic dose of that agent for at least 4–9 months after achieving full remission.

Maintenance phase1

- Those patients who have not relapsed in the acute or continuation phase proceed to the maintenance phase. It is generally recommended to use the same therapeutic agent as in the previous phases.

Discontinuation phase1

- If maintenance-phase treatment is not indicated, stable patients may be considered for discontinuation of treatment after the continuation phase. The precise timing and method of discontinuing psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder have not been systematically studied. Therefore, multiple patient related factors need to be considered as under before treatment discontinuation.

- Persistence of subthreshold depressive symptoms

- Prior history of multiple episodes of major depressive disorder

- Severity of initial and any subsequent episodes

- Earlier age at onset

- Presence of an additional nonaffective psychiatric diagnosis

- Presence of a chronic general medical disorder

- Family history of psychiatric illness, particularly mood disorder

- Ongoing psychosocial stressors or impairment

- Negative cognitive style

- Persistent sleep disturbances

Relevance of the APA clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with panic disorder to our medicine: Zoloft® (sertraline)

Panic disorder is a common and often disabling mental disorder. Treatment is indicated when symptoms of the disorder interfere with functioning or cause significant distress.2

Relevant aspects of the recommendations:

Principles of psychiatric management2

Consists of a comprehensive array of activities and interventions that should be instituted for all patients with panic disorder, in combination with specific modalities that have demonstrated efficacy. Unless indicated otherwise, the level of evidence for each of the following recommendations is category [I]

1- Establishing a therapeutic alliance: attention to the patient’s preferences and concerns with regard to treatment, education, support through phases of treatment.

2- Performing the psychiatric assessment: Patients should receive a thorough diagnostic evaluation both to establish the diagnosis of panic disorder and to identify other psychiatric or general medical conditions.

3- Tailoring the treatment plan for the individual patient: match the needs of the patient requires a careful assessment of the frequency and nature of the symptoms and a continuing evaluation and management of co-occurring psychiatric and/or medical conditions.

4- Evaluating the safety of the patient: A careful assessment of suicide risk is necessary.

5- Evaluating types and severity of functional impairment: panic disorder can impact life (work, school, family, social relationships, and leisure activities). The aim is a treatment plan intended to minimize the impairment.

6- Establishing goals for treatment: to reduce the frequency and intensity of panic attacks, anticipatory anxiety, and agoraphobic avoidance, optimally with full remission of symptoms and return to a premorbid level of functioning. Treatment of co-occurring psychiatric disorders is an additional goal.

7- Monitoring the patient’s psychiatric status: Psychiatrists may consider using rating scales and patients also can be asked to keep a daily diary of panic symptoms.

8- Providing education to the patient and, when appropriate, to the family: the patient should be informed of the diagnosis and educated about panic disorder and treatment options.

9- Coordinating the patient’s care with other clinicians: the clinicians should communicate periodically to ensure that care is coordinated and that treatments are working in synchrony.

10- Enhancing treatment adherence: the psychiatrist should assess and acknowledge potential barriers to treatment adherence and should work collaboratively with the patient to minimize their influence.

11- Working with the patient to address early signs of relapse: Patients should be reassured those fluctuations in symptoms can occur during the course of treatment.

Formulation and Implementation of a Treatment Plan2

1- Choosing a treatment setting: The treatment of panic disorder is generally conducted entirely on an outpatient basis, as the condition by itself rarely warrants hospitalization.2

2- Choosing an initial treatment modality: A range of specific psychosocial and pharmacological interventions have proven benefits in treating panic disorder.2

Initial treatment for Panic Disorder2

The use of:

- A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)

- A serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI)

- A tricyclic antidepressant (TCA),

- A benzodiazepine (appropriate as monotherapy only in the absence of a co-occurring mood disorder) or Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as the initial treatment for panic disorder is strongly supported by demonstrated efficacy in numerous randomized controlled trials.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend any of these pharmacological or psychosocial interventions as superior to the others, or to routinely recommend a combination of treatments over monotherapy (II).2

Considerations that guide the choice of an initial treatment2

- Patient preference

- Risks and benefits for the particular patient

- Patient’s past treatment history

- Presence of co-occurring general medical and other psychiatric conditions

- Cost

- Treatment availability

3- Evaluating whether the treatment is working: is important to monitor change in key symptoms such as frequency and intensity of panic attacks, level of anticipatory anxiety, degree of agoraphobic avoidance, severity of interference and distress related to panic disorders and co-occurring conditions. Rating scales are a useful adjunct to ongoing clinical assessment.2

4- Determining if and when to change treatment: If the response is unsatisfactory, the psychiatrist should first consider the possible contribution of untreated medical illness, co-occurring medical or psychiatric conditions, inadequate adherence, problems in the therapeutic alliance, psychosocial stressors, motivational factors, and inability to tolerate a particular treatment.2

If response to treatment remains unsatisfactory, it is appropriate to consider a change. Decisions about changes will depend on the level of response to the initial treatment, the palatability and feasibility of other treatment options for a given patient, and the level of symptoms and impairment that remain.2

5- Approaches to try when a first-line treatment is unsuccessful:2

- Augment the current treatment by adding another agent (in the case of pharmacotherapy) or another modality (i.e CBT if the patient is already receiving pharmacotherapy, or

- Switch to a different medication or therapeutic modality or add pharmacotherapy if the patient is already receiving CBT.

- If one first-line treatment (e.g., CBT, an SSRI, an SNRI) has failed, adding or switching to another first-line treatment is recommended.

- Adding a benzodiazepine to an antidepressant is a common augmentation strategy to target residual symptoms (II)

- If the treatment options with the most robust evidence have been unsuccessful, other options with some empirical support can be considered (e.g., a monoamine oxidase inhibitor [MAOI], Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy [PFPP]). (II)

6- Specific psychosocial interventions: Based on the current available evidence, CBT is the psychosocial treatment that would be indicated most often for patients. (II) Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy also has demonstrated efficacy for panic disorder, although its evidence base is more limited. (II)2

7- Specific pharmacological interventions:2

Because SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, and benzodiazepines appear roughly comparable in their efficacy for panic disorder, selecting a medication for a particular patient mainly involves considerations of side effects.

The relatively favorable safety and side effect profile of SSRIs and SNRIs makes them the best initial choice for many patients with panic disorder2

SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs are all preferable to benzodiazepines as monotherapies for patients with co-occurring depression or substance use disorders.

Maintaining or Discontinuing Treatment After Response2

Pharmacotherapy should generally be continued for 1 year or more after acute response to promote further symptom reduction and decrease risk of recurrence.2

If a decision is made to discontinue successful treatment with an SSRI, an SNRI, or a TCA, the medication should be gradually tapered (e.g., one dosage step down every month or two), thereby providing the opportunity to watch for recurrence and, if desired, to reinitiate treatment at a previously effective dose.2

The approach to benzodiazepine discontinuation also involves a slow and gradual tapering of dose, probably over 2–4 months and at rates no higher than 10% of the dose per week. CBT may be added to facilitate withdrawal from benzodiazepines.2

SERTRALINE2

Results from a number of large RCTs demonstrate the efficacy of sertraline for the acute and long-term treatment of panic disorder. Results from a fixed-dose randomized controlled trial of 50 mg/day, 100 mg/day, or 200 mg/day of sertraline showed significantly greater reduction for the SSRI, compared to placebo, on measures of panic and anxiety, without evidence of a dose-response relationship.

Rapaport and associates examined the long-term efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder. Patients received 52 weeks of open-label sertraline treatment followed by a 28-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation trial. Compared to those blindly tapered and switched to placebo, patients who continued to receive sertraline were less likely to have an exacerbation of panic symptoms (13% vs. 33%) or discontinue the study because of insufficient clinical response (12% vs. 24%).

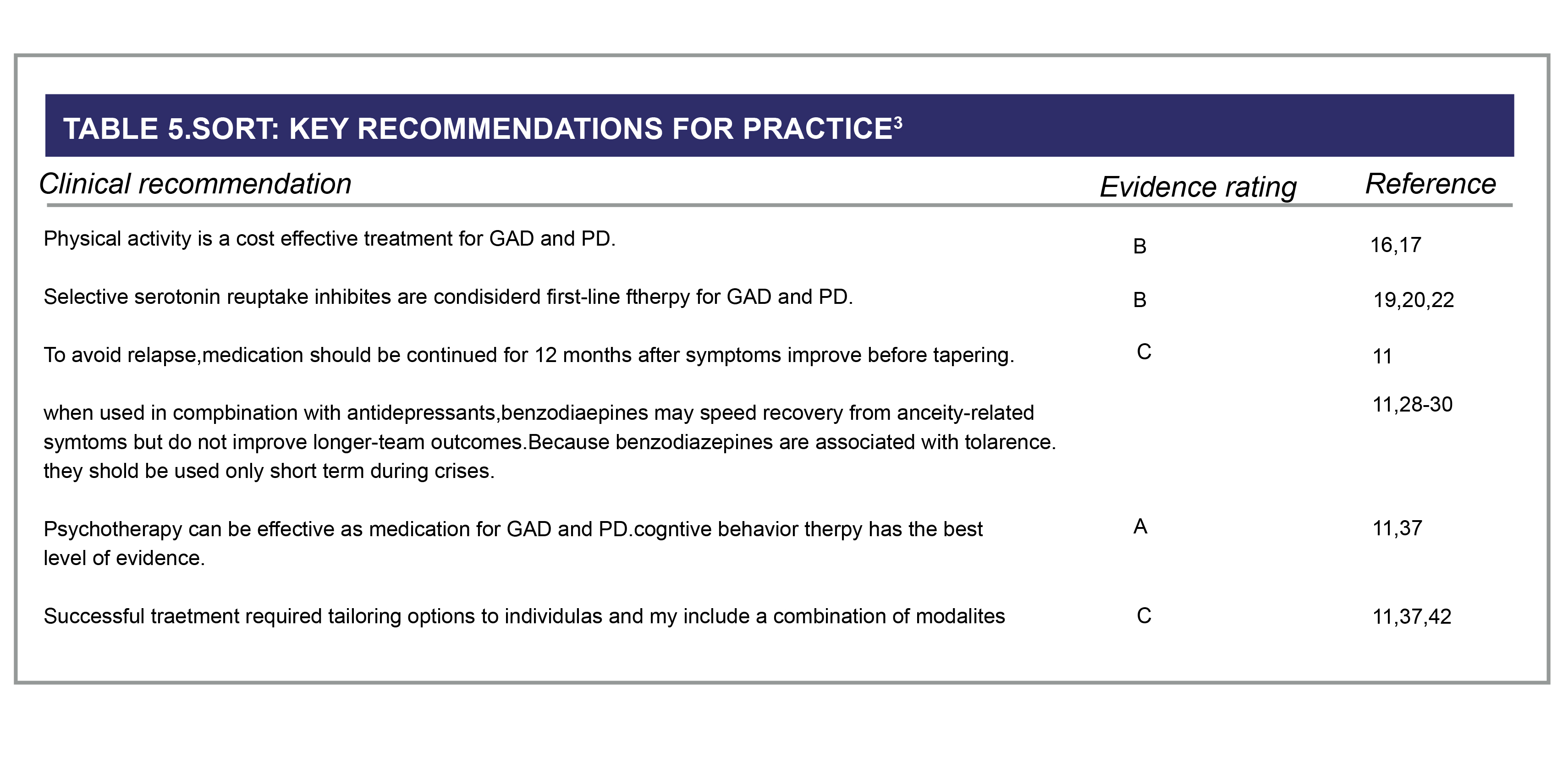

Relevance of the American Academy of Family Physicians’ guidance on the Diagnosis and Management of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults.

This is a key initial guidance document for primary care physicians (family doctors or general practitioners)

GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; PD = panic disorder. A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-oriented evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to http://www.aafp.org/afpsort

Presentation3

Patients with GAD typically present with excessive anxiety about ordinary, day-today situations. The anxiety is intrusive, causes distress or functional impairment, and often encompasses multiple domains (e.g., finances, work, health). The anxiety is often associated with physical symptoms, such as sleep disturbance, restlessness, muscle tension, gastrointestinal symptoms, and chronic headaches.

PD is characterized by episodic, unexpected panic attacks that occur without a clear trigger. Panic attacks are defined by the rapid onset of intense fear (typically peaking within about 10 minutes) with at least four of the physical and psychological symptoms in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Another requirement for the diagnosis of PD is that the patient worries about further attacks or modifies his or her behavior in maladaptive ways to avoid them. The most common physical symptom accompanying panic attacks is palpitations.

Evaluation3

When evaluating a patient for a suspected anxiety disorder, it is important to exclude medical conditions with similar presentations (e.g., endocrine conditions; cardiopulmonary conditions; neurologic diseases) and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., other anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder); and use of substances such as Caffeine, albuterol, Levothyroxine or decongestants; or substance withdrawal may also present with similar symptoms and should be ruled out.

Management considerations3

- Medication or psychotherapy is a reasonable initial treatment option for GAD and PD

- Compassionate listening and education are an important foundation in the treatment of anxiety disorders

- Common lifestyle recommendations that may reduce anxiety-related symptoms include identifying and removing possible triggers

MEDICATIONS3

First-Line Therapies.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally considered first-line therapy for GAD and PD.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are better studied for PD, but are thought to be effective for both GAD and PD. In the treatment of PD, TCAs are as effective as SSRIs, but adverse effects may limit the use of TCAs in some patients

- Venlafaxine, extended release, is effective and well tolerated for GAD and PD, whereas duloxetinehas been adequately evaluated only for GAD

- Mixed evidence suggests bupropion may have anxiogenic effects for some patients, thus warranting close monitoring if used for treatment of comorbid depression, seasonal affective disorder, or smoking cessation. Bupropion is not approved for the treatment of GAD or PD

- Because of the typical delay in onset of action, medications should not be considered ineffective until they are titrated to the high end of the dose range and continued for at least four weeks.

- Once symptoms have improved, medications should be used for 12 months before tapering to limit relapse

- Benzodiazepines are effective in reducing anxiety, but there is a dose-response relationship associated with tolerance, sedation, confusion, and increased mortality.

- NICE guidelines recommend only short-term of benzodiazepines use during crises.

*Initial Treatment:4

Depression and QCD: Sertraline treatment should be started at a dose of 50 mg/day.

Panic Disorder, PTSD, and social anxiety disorder: Therapy should be initiated at 25 mg/day.Titration:4

Depression, OCD, Panic Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder and PTSD:

Patients not responding to a 50 mg dose may benefit from dose increase. Dose changes should be made In steps of 50 mg at intervals of at least one week, up to a maximum of 200 mg/day. Changes in dose should not be made more frequently than once per week.

References:

- PRACTICE Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Accessed on: March 2024.

- Practice Guideline For The Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder. Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed on: March 2024.

- Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):617-24.

- ZOLOFT® (Sertraline), SmPC, May 2022

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

Clinical Information

The following publications provide useful and detailed information on the treatment with Zoloft®

Efficacy and tolerability

Cipriani A et al Lancet 2009;373 (9665):746-758

Clinically important differences exist between commonly prescribed antidepressants for both efficacy and acceptability in favour of escitalopram and sertraline. Sertraline might be the best choice when starting treatment for moderate to severe major depression in adults because it has the most favourable balance between benefits, acceptability, and acquisition cost.1

Lowe B et al J affect disord 2005; 87(2-3):271 -279

For treatment of depressive disorders in routine outpatient settings, sertraline is safe and efficacious. Patients without prior episodes of depression, without medical comorbidity, and those with higher levels of depression-related functional limitations are most likely to respond to sertraline treatment.2

Sheikh JI et al J Am Geriatric Soc 2004; 52 (1) :86-92

To report on the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sertraline in the treatment of elderly depressed patients with and without comorbid medical illness3

Efficacy and tolerability in Comorbidities

Glassman AH et al JAMA 2002: 288(6): 701-709

Major depressive disorder (MDD) occurs in 15% to 23% of patients with acute coronary syndromes and constitutes an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality. However, no published evidence exists that antidepressant drugs are safe or efficacious in patients with unstable ischemic heart disease.4

O’Connor CM et al J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56 (9): 692-699

The objective was to test the hypothesis that heart failure (HF) patients treated with sertraline will have lower depression scores and fewer cardiovascular events compared with placebo.5

Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. JAMA. 2003;289:3106-3116

Depression and low perceived social support (LPSS) after myocardial infarction (MI) are associated with higher morbidity and mortality, but little is known about whether this excess risk can be reduced through treatment.6

Rasmussen A, Lunde M, Poulsen DL, Sørensen K, Qvitzau S, Bech P. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the prevention of depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics. 2003 May-Jun;44(3):216-21.

The authors tested the effect of sertraline in the prevention of poststroke depression.7

Yeh et al J Eval Clin Pract. 2019 : 1-9

Alprazolam usage in patients with hypertension was associated with a slightly reduced risk of MACEs and all-cause mortality, and up to 22% reduced risk of hemorrhagic stroke was observed in alprazolam users aged <65 years.8

References:

- Cipriani A, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. 2009;373(9665):746-58.

- Löwe B, et al. Efficacy, predictors of therapy response, and safety of sertraline in routine clinical practice: prospective, open-label, non-interventional postmarketing surveillance study in 1878 patients. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):271-9.

- Sheikh JI, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sertraline in patients with late-life depression and comorbid medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 004;52(1):86-92.

- Glassman AH, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288(6):701-9.

- O'Connor CM, et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(9):692-9.

- Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3106-16.

- Rasmussen A, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the prevention of depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):216-21.

- Yeh CB, et al. Association of alprazolam with major cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(3):983-991.

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

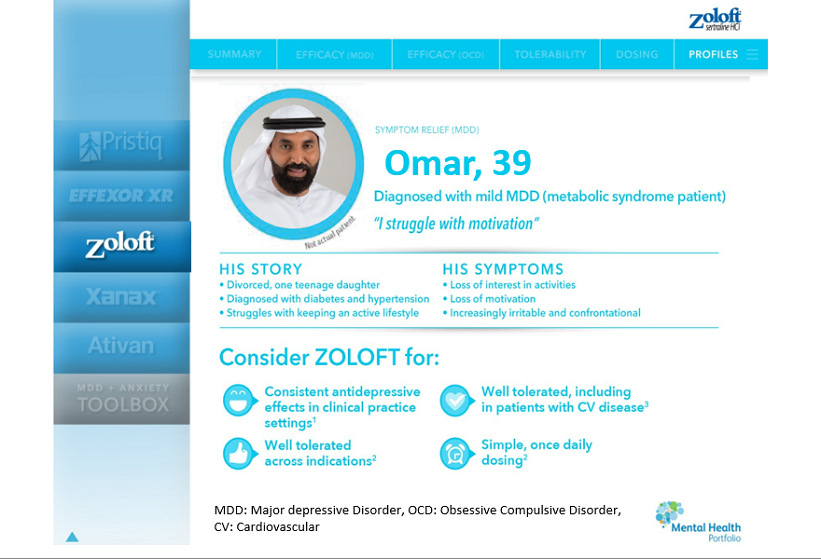

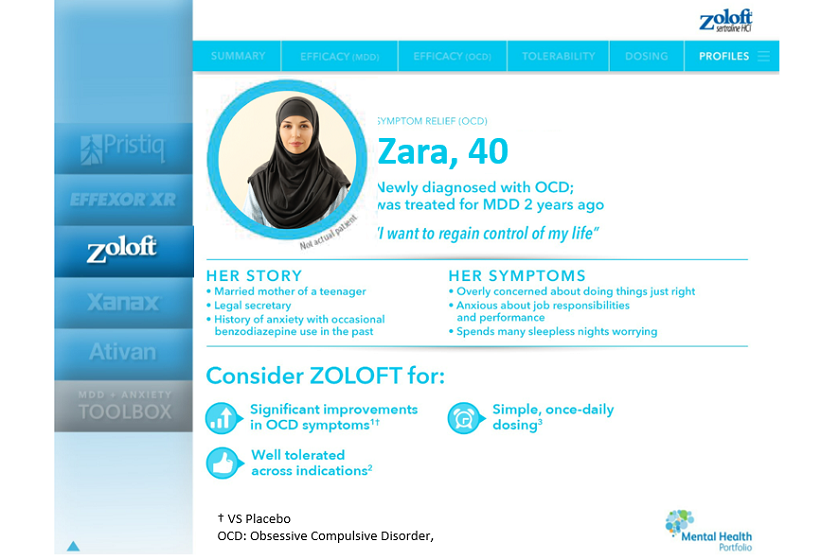

Patient Profiles

Zoloft® is indicated in for the treatment of:1

- Major depressive episodes. Prevention of recurrence of major depressive episodes.

- Panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in adults and paediatric patients aged 6-17 years.

- Social anxiety disorder.

- Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

The following patient profiles show typical examples where Zoloft® could be considered to treat MDD.

*Our examples are fictitious patients. May not be representative of all patients.

References:

- ZOLOFT® (Sertraline), SmPC, May 2022

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00004

Full Prescribing information

GLI-ZOLO-2024-00006